Your bird's most precious possession is its feathers. Each feather on a bird's body is a finely tuned structure that enables flight in some birds, helps them show off to potential mates, blend into their surroundings, protect the skin and keep them warm. However, after about a year, these delicate structures get worn out. Even the most careful preening will cause feathers to fray, feathers get crimped and thin from even daily activities such as egg-laying, mating, brooding, etc... Feathers that are broken and worn out are not able to insulate the bird against the elements of wind, rain, and snow which accompany the cooler or winter season.

Molting is a natural necessary process that replaces all these old feathers and also gives the bird time to stock up on their nutrient reserves from egg-laying and mating. Just how many feathers does a chicken have to molt? Quite a few, most standard breeds carry around approximately 8,000 feathers! The entire process of replacing their feathers can last from 8 to 12 weeks or longer.

Just what are feathers?

Feathers start out as live "pinfeathers" or "blood feathers" with a blood supply and look like tiny pins or quills poking through the skin. Pin feathers are encased with a Keratin coating or Feather Sheath. Once the feather has reached its genetically determined length, the blood supply is cut off and the feather is considered a dead unit in the skin.

There are many types of feathers that adorn a chicken's body, each structured differently and serve a different purpose, these are the most common of feathers.

1. Down feathers: These are the insulating feathers, very fine, soft, hair-like feathers that are found beneath the heavier feathers of the body. Many of these feathers can be found on the abdomen of the bird to trap air and keep the bird warm.

2. Contour feathers: These feathers are the outermost feathers of the bird covering wings, tail, and body. They make up the shape of the bird and can be used to determine the breed. Contour feathers have a heavy shaft with barbs branching off from the shaft. Tiny barbules radiate from the barbs which interlock together to create a smooth plane. Some breeds such as Silkies have a more delicate feather shaft with unusually long barbs, the barbules are elongated and arranged irregularly giving them a soft fluffy appearance. Frizzle feathers grow out and curly rather than flat and smooth.

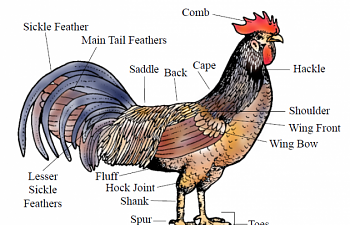

3. Hackle, Sickle, and Saddle feathers: Both hens and roosters have hackle and saddle feathers. However, these feathers grow longer on roosters. Hackle feathers can be found around the neck, saddle feathers are found in front of the tail. Sickle feathers are the long, curly, showy feathers on the tail of the rooster.

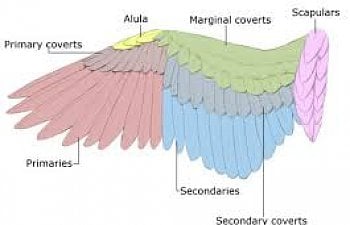

4. Primaries: The strongest of feathers, these flight feathers are the outermost feathers attached to the "hand" of the wings and are called Primaries. Most chicken breeds have 10 primary feathers and 14 secondary feathers. Secondary feathers are the inner flight feathers positioned behind the primaries and grow out of the forearm. These provide lift, the ability to flap and soar.

5. Semiplumes: They are similar to downy feathers but longer and less full. These feathers are found hidden between the Contour feathers. These smaller feathers help to keep the bird smooth and streamlined in appearance and also add insulation

6. Filoplumes: These are located at the base of the contour feathers and are hair-like in appearance with a tuft of barbs at the top. These feathers lack the muscle attachment like contour feathers have, however, filoplumes are supplied with nerve endings that react to help keep the contour feathers in place.

7. Coverts: Covert feathers, as the name implies, are feathers that cover other feathers. They help smooth airflow over the wings and body for flight. Chickens have Ear, Wing, and Tail Covert feathers.

What causes them to molt?

What causes a bird to molt has intrigued scientists for a long time. It is a very complex process that has been difficult to completely sort out and understand. However, the one thing they do know is that there is a rhythm that governs the molting process.

Deep inside your bird's brain in the Pineal Gland is a clock, all birds have one. It is called their diurnal, circadian or photoperiodic clock and it keeps track of the hours of the day. It is also a calendar clock, in that it keeps very accurate track of the month of the year. Within the Pineal Gland is a group of cells that automatically oscillate, ticking like a metronome. The Pineal Gland is wired to the birds' eyes to perceive and sense light. This clock informs the bird when it is time to breed and molt. The bird’s circadian clock ticks from the hatch. But to remain accurate over time, its hands need to be fine-tuned from clues obtained from the environment around it. It receives these clues in the form of sunlight and the length of the days. The process of resetting the clock to an exact time is called entrainment.

And what winds this clock?

The circadian clock responds best to certain wavelengths of light and also to some extent, to the light’s intensity. But most important it seems, is the shape of the light-length curve during the year. Ordinary white sunlight or ‘full spectrum light’ contains all the colors of the rainbow. But within this rainbow of colors, the circadian clock responds best to red light (about 640nm).

Molting Triggers:

The most common trigger for molting is a decrease of daylight hours and the end of an egg-laying cycle, which typically coincide with late summer or early fall. These shorter days tell the internal clock it's time to stop laying and begin to molt off all those old feathers. However, there are several less innocuous molting causes as well. Physical stress, a lack of water, malnutrition, extreme heat, hatching a clutch of eggs and unusual lighting conditions (owner has a light bulb in the coop emitting light all night and then suddenly removes the constant light source) can all be at the root of an unexpected or untimely molt. Broodies will mini molt after going broody, whether they have hatched chicks or not, nature will tell them to replace their feathers that might possibly have become too frayed during chick raising.

Do new feathers push the old feathers out?

It is not that simple. The key to new feather formation is the removal of the old feather. The presence of a well-anchored feather prevents a new feather from forming. When that feather loosens or is plucked out, a new feather immediately begins to form. Prior to molting, the blood vessels supporting the old feather dry up, and feather attachment to the surrounding tissue becomes loosened and the feather falls out. At this point, a new feather will begin to grow.

Is there an order in which feathers fall out?

Yes, there is. When feathers are molted out normally, an equal amount of feathers are lost from both sides of the body in the same spots. Primaries and secondaries are molted equally and slowly so the bird continues to have the ability to fly. Old feathers protect pin feathers and the bird is able to maintain a healthy body temperature.

The molting process:

Chickens will usually but not always start molting at the head and neck, then down the back, across the breast and thighs, vent area, wings, and finally their tail feathers. Some birds drop their feathers fast and furious, feathers just raining off the bird, leaving large bare patches in places on the body. These types usually finish up the molt earlier. Others molt at a much slower pace, dragging out the molt for months on end. Some people say their birds have never molted. I am not so sure I believe this as no breed has feathers impervious to breakage and wearing out. But what may really be happening is the bird is on a completely different schedule for molting, dropping a feather here and there all throughout the year, (some Parrots molt in this fashion) nearly going undetected by their owners that they are molting at all, never losing enough protein to stop laying or they lay fewer eggs during these times.

What hormones play a part in molting?

Scientists know what hormones are in play when molt occurs. But they do not know the process by which they cause old feathers to fall and new feathers to replace them.

1. Cytokines:

Cytokines are messenger proteins that carry signals locally between cells. These signaling molecules are used extensively by birds in cellular communication. Unlike hormones, they concentrate locally and are active in a lower concentration. These signaling chemicals have been found to increase when a molt begins. Whether they function to dislodge the old feather or grow a feather or if they are the actual cause of the molting process remains unknown.

2. Melatonin:

Melatonin tells the bird when to molt, however, it does not cause the feathers to fall out or regrow. It is the primary hormone produced by the Pineal Gland. It is also called the "timekeeper hormone" because oscillations in its production and secretions are timed to the amount of light that is presently being the body's central timekeeper. Its presence or absence controls the production of all other hormones involved in reproduction and molt as well as all differences between day and nighttime activities. Melatonin is secreted when it is dark. Daily melatonin production is longest in the winter when nights are long, and shortest in the summer when nights are short. Levels of melatonin in the blood reach their highest daily peaks in the spring and summer when days are lengthening and its lowest peaks are in the fall and winter.

Melatonin rhythm and amplitude govern the production of many hormones produced in the bird's pituitary gland. These include FSH, LH, and Prolactin, which are involved in nesting and reproduction, ACTH which controls adrenal gland hormone production, TSH which controls thyroid hormone production, and GH which controls growth.

3. LH (Luteinizing Hormone)

In female birds, this hormone stimulates ovulation. In male birds, it stimulates testosterone production. In response to lowering levels of melatonin in the lengthening springtime days, blood levels of LH increase and trigger their reproductive cycle. As their reproductive cycle ends, the LH levels decline. This decline occurs concurrently with their molt.

4. Prolactin (PRL)

Prolactin is another hormone produced by the bird's Pituitary Gland under the control of the Pineal Gland. Some studies indicate that prolactin levels are highest in the period that birds begin their molt.

5. Progesterone:

Progesterone is produced by the ovaries of birds as they go through their reproductive period. Birds that do not produce enough Depopovera or Progestin can completely skip a molt. Too much progesterone and not enough progestin will not allow the laying cycle to shut off, nor the bird to molt.

6. Thyroxine (Thyroid hormone):

Thyroxine may or may not cause molt. Some veterinarians associate molt problems with thyroid trouble hence removing thyroid glands of Parrots with molting issues. Thyroid hormone level goes up with feathers being formed and even when birds are cold. It is definitely associated with molt given the high levels of thyroxine causes chickens to molt. The thyroid produces hormones that regulate the body's metabolic rate as well as heart and digestive function, muscle control, brain development, mood, and bone maintenance. Its correct functioning depends on having a good supply of iodine from the diet.

So what can we do to assure a good molt?

Make sure to keep your birds on a good well-balanced diet all year long, especially during a molt. A poor diet lacking in high protein, certain vitamins, and minerals can cause poor feather growth, harder, longer molts, or skipping a molt altogether. During molting season you may want to switch to a Flock Raiser type feed which is usually a bit higher in protein than layer feed. It also lacks all the calcium that layer feed has, hens will not need the high calcium and too much calcium can affect the kidneys. I have found Chick Starter to be a wonderful feed for molting hens. Generally around 18% protein, it has all they need to grow a good set of feathers. You can add other foodstuffs such as cooked ground turkey or beef. Meat is loaded with proteins and amino acids, essential for good feathering. Feathers are made up of 85% to 90% Keratin, a structural protein. And the only way to get this much protein to grow all these feathers is via their food. Always give them a high protein diet during this stressful time, limit scratch and treats during this time as to not dilute their high protein diet.

Molting also gives the bird time to build up its nutrient reserves from all the egg-laying or mating. These activities are draining to the bird's bodily stash of nutrients, this short respite from the breeding season will rejuvenate them for the following season.

Make sure they always have plenty of water. This will not only avoid causing a molt but will keep chickens laying when they should be. Becoming dehydrated is very detrimental to their health.

Molting can be stressful on birds. They feel vulnerable and may not want to venture outside. You may notice a personality change in your birds. A once confident bird can turn extremely shy, others may become more cranky and ornery. Molting takes a ton of energy to regrow all these feathers. The hormonal dips and surges can cause diarrhea, inappetence, fluffed up appearance, and general malaise. Combs will pale to signal this non-fertile period.

Try to avoid picking up a molting bird unless absolutely necessary. You can accidentally break blood feathers and cause bleeding, all those pin feathers are prickly and can cause pain and just the stress alone being picked up when they don't want to be picked up can cause poor feather growth. Keep stress down all around the coop when they are all molting.

Sometimes birds choose to molt on the coldest day of winter and there isn't anything you can do about it. Their internal clocks have decided, this is the day! If I feel a bird is very cold during this time, I have offered up some temporary heat that day although I don't like to keep them in it for too long so as to change their body chemistry. But a blast of heat can once in a while, on those brutally cold winter days, help a molting bird get through the worst of it. Generally, they manage just fine without any heat assistance, however. Use your own judgment.

I hope this article has helped you understand the process of molting a bit better. It can be a tough time for chickens to get through, but with a bit more attention paid to this necessary function, you can better help your birds through it.

Please stop by the following links for further reading:

Molting threads and articles:

https://www.backyardchickens.com/articles/chickens-loosing-feathers-managing-your-flocks-molt.64576/

https://www.backyardchickens.com/articles/what-happens-when-chickens-molt.67366/

https://www.backyardchickens.com/threads/some-molting-facts.1274389/

Protein and feeding during a molt:

https://www.backyardchickens.com/threads/3-tips-to-help-hens-through-molt.1139523/

https://www.backyardchickens.com/th...eather-regrowth-with-proper-nutrition.828722/

BYC Worst Chicken Molt Contests:

https://www.backyardchickens.com/th...st-your-best-worst-chicken-molt-pics.1269409/

https://www.backyardchickens.com/th...st-your-best-worst-chicken-molt-pics.1197023/

Molting is a natural necessary process that replaces all these old feathers and also gives the bird time to stock up on their nutrient reserves from egg-laying and mating. Just how many feathers does a chicken have to molt? Quite a few, most standard breeds carry around approximately 8,000 feathers! The entire process of replacing their feathers can last from 8 to 12 weeks or longer.

Just what are feathers?

Feathers start out as live "pinfeathers" or "blood feathers" with a blood supply and look like tiny pins or quills poking through the skin. Pin feathers are encased with a Keratin coating or Feather Sheath. Once the feather has reached its genetically determined length, the blood supply is cut off and the feather is considered a dead unit in the skin.

There are many types of feathers that adorn a chicken's body, each structured differently and serve a different purpose, these are the most common of feathers.

1. Down feathers: These are the insulating feathers, very fine, soft, hair-like feathers that are found beneath the heavier feathers of the body. Many of these feathers can be found on the abdomen of the bird to trap air and keep the bird warm.

2. Contour feathers: These feathers are the outermost feathers of the bird covering wings, tail, and body. They make up the shape of the bird and can be used to determine the breed. Contour feathers have a heavy shaft with barbs branching off from the shaft. Tiny barbules radiate from the barbs which interlock together to create a smooth plane. Some breeds such as Silkies have a more delicate feather shaft with unusually long barbs, the barbules are elongated and arranged irregularly giving them a soft fluffy appearance. Frizzle feathers grow out and curly rather than flat and smooth.

3. Hackle, Sickle, and Saddle feathers: Both hens and roosters have hackle and saddle feathers. However, these feathers grow longer on roosters. Hackle feathers can be found around the neck, saddle feathers are found in front of the tail. Sickle feathers are the long, curly, showy feathers on the tail of the rooster.

4. Primaries: The strongest of feathers, these flight feathers are the outermost feathers attached to the "hand" of the wings and are called Primaries. Most chicken breeds have 10 primary feathers and 14 secondary feathers. Secondary feathers are the inner flight feathers positioned behind the primaries and grow out of the forearm. These provide lift, the ability to flap and soar.

5. Semiplumes: They are similar to downy feathers but longer and less full. These feathers are found hidden between the Contour feathers. These smaller feathers help to keep the bird smooth and streamlined in appearance and also add insulation

6. Filoplumes: These are located at the base of the contour feathers and are hair-like in appearance with a tuft of barbs at the top. These feathers lack the muscle attachment like contour feathers have, however, filoplumes are supplied with nerve endings that react to help keep the contour feathers in place.

7. Coverts: Covert feathers, as the name implies, are feathers that cover other feathers. They help smooth airflow over the wings and body for flight. Chickens have Ear, Wing, and Tail Covert feathers.

What causes them to molt?

What causes a bird to molt has intrigued scientists for a long time. It is a very complex process that has been difficult to completely sort out and understand. However, the one thing they do know is that there is a rhythm that governs the molting process.

Deep inside your bird's brain in the Pineal Gland is a clock, all birds have one. It is called their diurnal, circadian or photoperiodic clock and it keeps track of the hours of the day. It is also a calendar clock, in that it keeps very accurate track of the month of the year. Within the Pineal Gland is a group of cells that automatically oscillate, ticking like a metronome. The Pineal Gland is wired to the birds' eyes to perceive and sense light. This clock informs the bird when it is time to breed and molt. The bird’s circadian clock ticks from the hatch. But to remain accurate over time, its hands need to be fine-tuned from clues obtained from the environment around it. It receives these clues in the form of sunlight and the length of the days. The process of resetting the clock to an exact time is called entrainment.

And what winds this clock?

The circadian clock responds best to certain wavelengths of light and also to some extent, to the light’s intensity. But most important it seems, is the shape of the light-length curve during the year. Ordinary white sunlight or ‘full spectrum light’ contains all the colors of the rainbow. But within this rainbow of colors, the circadian clock responds best to red light (about 640nm).

Molting Triggers:

The most common trigger for molting is a decrease of daylight hours and the end of an egg-laying cycle, which typically coincide with late summer or early fall. These shorter days tell the internal clock it's time to stop laying and begin to molt off all those old feathers. However, there are several less innocuous molting causes as well. Physical stress, a lack of water, malnutrition, extreme heat, hatching a clutch of eggs and unusual lighting conditions (owner has a light bulb in the coop emitting light all night and then suddenly removes the constant light source) can all be at the root of an unexpected or untimely molt. Broodies will mini molt after going broody, whether they have hatched chicks or not, nature will tell them to replace their feathers that might possibly have become too frayed during chick raising.

Do new feathers push the old feathers out?

It is not that simple. The key to new feather formation is the removal of the old feather. The presence of a well-anchored feather prevents a new feather from forming. When that feather loosens or is plucked out, a new feather immediately begins to form. Prior to molting, the blood vessels supporting the old feather dry up, and feather attachment to the surrounding tissue becomes loosened and the feather falls out. At this point, a new feather will begin to grow.

Is there an order in which feathers fall out?

Yes, there is. When feathers are molted out normally, an equal amount of feathers are lost from both sides of the body in the same spots. Primaries and secondaries are molted equally and slowly so the bird continues to have the ability to fly. Old feathers protect pin feathers and the bird is able to maintain a healthy body temperature.

The molting process:

Chickens will usually but not always start molting at the head and neck, then down the back, across the breast and thighs, vent area, wings, and finally their tail feathers. Some birds drop their feathers fast and furious, feathers just raining off the bird, leaving large bare patches in places on the body. These types usually finish up the molt earlier. Others molt at a much slower pace, dragging out the molt for months on end. Some people say their birds have never molted. I am not so sure I believe this as no breed has feathers impervious to breakage and wearing out. But what may really be happening is the bird is on a completely different schedule for molting, dropping a feather here and there all throughout the year, (some Parrots molt in this fashion) nearly going undetected by their owners that they are molting at all, never losing enough protein to stop laying or they lay fewer eggs during these times.

What hormones play a part in molting?

Scientists know what hormones are in play when molt occurs. But they do not know the process by which they cause old feathers to fall and new feathers to replace them.

1. Cytokines:

Cytokines are messenger proteins that carry signals locally between cells. These signaling molecules are used extensively by birds in cellular communication. Unlike hormones, they concentrate locally and are active in a lower concentration. These signaling chemicals have been found to increase when a molt begins. Whether they function to dislodge the old feather or grow a feather or if they are the actual cause of the molting process remains unknown.

2. Melatonin:

Melatonin tells the bird when to molt, however, it does not cause the feathers to fall out or regrow. It is the primary hormone produced by the Pineal Gland. It is also called the "timekeeper hormone" because oscillations in its production and secretions are timed to the amount of light that is presently being the body's central timekeeper. Its presence or absence controls the production of all other hormones involved in reproduction and molt as well as all differences between day and nighttime activities. Melatonin is secreted when it is dark. Daily melatonin production is longest in the winter when nights are long, and shortest in the summer when nights are short. Levels of melatonin in the blood reach their highest daily peaks in the spring and summer when days are lengthening and its lowest peaks are in the fall and winter.

Melatonin rhythm and amplitude govern the production of many hormones produced in the bird's pituitary gland. These include FSH, LH, and Prolactin, which are involved in nesting and reproduction, ACTH which controls adrenal gland hormone production, TSH which controls thyroid hormone production, and GH which controls growth.

3. LH (Luteinizing Hormone)

In female birds, this hormone stimulates ovulation. In male birds, it stimulates testosterone production. In response to lowering levels of melatonin in the lengthening springtime days, blood levels of LH increase and trigger their reproductive cycle. As their reproductive cycle ends, the LH levels decline. This decline occurs concurrently with their molt.

4. Prolactin (PRL)

Prolactin is another hormone produced by the bird's Pituitary Gland under the control of the Pineal Gland. Some studies indicate that prolactin levels are highest in the period that birds begin their molt.

5. Progesterone:

Progesterone is produced by the ovaries of birds as they go through their reproductive period. Birds that do not produce enough Depopovera or Progestin can completely skip a molt. Too much progesterone and not enough progestin will not allow the laying cycle to shut off, nor the bird to molt.

6. Thyroxine (Thyroid hormone):

Thyroxine may or may not cause molt. Some veterinarians associate molt problems with thyroid trouble hence removing thyroid glands of Parrots with molting issues. Thyroid hormone level goes up with feathers being formed and even when birds are cold. It is definitely associated with molt given the high levels of thyroxine causes chickens to molt. The thyroid produces hormones that regulate the body's metabolic rate as well as heart and digestive function, muscle control, brain development, mood, and bone maintenance. Its correct functioning depends on having a good supply of iodine from the diet.

So what can we do to assure a good molt?

Make sure to keep your birds on a good well-balanced diet all year long, especially during a molt. A poor diet lacking in high protein, certain vitamins, and minerals can cause poor feather growth, harder, longer molts, or skipping a molt altogether. During molting season you may want to switch to a Flock Raiser type feed which is usually a bit higher in protein than layer feed. It also lacks all the calcium that layer feed has, hens will not need the high calcium and too much calcium can affect the kidneys. I have found Chick Starter to be a wonderful feed for molting hens. Generally around 18% protein, it has all they need to grow a good set of feathers. You can add other foodstuffs such as cooked ground turkey or beef. Meat is loaded with proteins and amino acids, essential for good feathering. Feathers are made up of 85% to 90% Keratin, a structural protein. And the only way to get this much protein to grow all these feathers is via their food. Always give them a high protein diet during this stressful time, limit scratch and treats during this time as to not dilute their high protein diet.

Molting also gives the bird time to build up its nutrient reserves from all the egg-laying or mating. These activities are draining to the bird's bodily stash of nutrients, this short respite from the breeding season will rejuvenate them for the following season.

Make sure they always have plenty of water. This will not only avoid causing a molt but will keep chickens laying when they should be. Becoming dehydrated is very detrimental to their health.

Molting can be stressful on birds. They feel vulnerable and may not want to venture outside. You may notice a personality change in your birds. A once confident bird can turn extremely shy, others may become more cranky and ornery. Molting takes a ton of energy to regrow all these feathers. The hormonal dips and surges can cause diarrhea, inappetence, fluffed up appearance, and general malaise. Combs will pale to signal this non-fertile period.

Try to avoid picking up a molting bird unless absolutely necessary. You can accidentally break blood feathers and cause bleeding, all those pin feathers are prickly and can cause pain and just the stress alone being picked up when they don't want to be picked up can cause poor feather growth. Keep stress down all around the coop when they are all molting.

Sometimes birds choose to molt on the coldest day of winter and there isn't anything you can do about it. Their internal clocks have decided, this is the day! If I feel a bird is very cold during this time, I have offered up some temporary heat that day although I don't like to keep them in it for too long so as to change their body chemistry. But a blast of heat can once in a while, on those brutally cold winter days, help a molting bird get through the worst of it. Generally, they manage just fine without any heat assistance, however. Use your own judgment.

I hope this article has helped you understand the process of molting a bit better. It can be a tough time for chickens to get through, but with a bit more attention paid to this necessary function, you can better help your birds through it.

Please stop by the following links for further reading:

Molting threads and articles:

https://www.backyardchickens.com/articles/chickens-loosing-feathers-managing-your-flocks-molt.64576/

https://www.backyardchickens.com/articles/what-happens-when-chickens-molt.67366/

https://www.backyardchickens.com/threads/some-molting-facts.1274389/

Protein and feeding during a molt:

https://www.backyardchickens.com/threads/3-tips-to-help-hens-through-molt.1139523/

https://www.backyardchickens.com/th...eather-regrowth-with-proper-nutrition.828722/

BYC Worst Chicken Molt Contests:

https://www.backyardchickens.com/th...st-your-best-worst-chicken-molt-pics.1269409/

https://www.backyardchickens.com/th...st-your-best-worst-chicken-molt-pics.1197023/